The current imbroglio over the Commonwealth’s buy back of water from a company formerly associated with a government minister has dominated the news now for some days. Amongst the commentary I have been left wondering about some assertions concerning the water entitlements at the heart of the deal.

Water regulation is an extremely complicated field at the intersection of science, conservation, policy, the market, and politics – and I don’t pretend to be an expert. However, in this very lawyerly post, I try to work out the general operation of the regulatory framework that underpins the drama, to try to isolate the legal questions.

The story

In August 2017, the Commonwealth Minister in charge of water, Barnaby Joyce, approved a Commonwealth buy back of water from a company called Eastern Australia Agriculture (‘EAA’) for approximately $80 million.

Until 2008 and before his entry into Parliament in 2013, Liberal MP and minister, Angus Taylor, had been a director and shareholder of EAA. After resigning, it appears that he had been a consultant to the company and associated also with its Cayman Islands registered parent-company.

It seems that the agreement to buy back the water did not go through the tender processes applied to other, similar arrangements where the Commonwealth would identify the need to acquire water entitlements to promote a particular environmental purpose, and call for expressions of interest. Further, the price paid appears to be higher than the expected market price of the water entitlements.

An independent report by the Australia Institute raised a number of questions about the transparency and appropriateness of the transaction. The report followed questions in Senate Estimates, posed by Senator Rex Patrick and the documents produced as a consequence.

The combination of the lack of a regular tender process, apparent payment above value, a government minister’s connection to the corporate recipient of the payment, and the company’s offshore registration, have attracted controversy. As a consequence, there have been calls for an independent inquiry or royal commission, and significant pressure placed on the former Water Minister and the PM.

What has puzzled me through this public discussion is the precise nature of the problems with the water buyback, which appear to conflate these diverse issues. I’m interested to understand whether there is a breach of the legislated water purchasing process, or whether it is more distaste about ostensible relationships between the parties, and ultimate off-shore profits: legitimate questions, but separate from the transaction itself.

To try to work through the issues, I have gone to the legislative and policy instruments to see how the process runs.

Water Licences (Queensland)

All rights to the use, flow and control of all water in Queensland are vested in the State. (s26, Water Act 2000 (Qld))

Further to this ownership, the State provides for licensing of both groundwater and surface water. This includes overland flows such as flood waters. Yes – if you want to collect or divert floodwaters on your land, you need to apply for a licence.

The owner of a parcel of land may apply for a licence for the taking and using of water on that land, or to interfere with the flow on the land. (s107, Water Act 2000 (Qld))

A licence for overland flow will state the location from which that water may be taken or interfered with (s117) and it may only be used on the land to which it relates (s119). While such rights are available to the owner of that land, there are a few other categories of permitted overland flow rights-holders – including a ‘prescribed entity’ (Water Act 2000 (Qld), s105). This term includes the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (‘CEWH’) established under the Water Act 2007 (Cth).

A licence holder may only deal with that licence (including transferring it) through application to the Chief Executive ie to the Queensland government. Permission for the transfer will only be given if the proposal to transfer the licence is in accordance with the relevant water plan.

The Water Plan (Condamine and Balonne) 2019 (Qld) relates to EAA’s property, located in the relevant district. (I realise that this Plan post-dates the relevant sale, but I’m assuming for now that the provisions are equivalent to those in 2017.) The Plan restricts taking overland flows without a licence (s37) and provides for the using of works to capture overland flow (s44). A licence must stipulate the maximum rate of taking, maximum storage works and volumetric limits of water taken (s48).

EAA, as the land owner of land within the Condamine and Balonne water district, must have held overland flow licences under the Water Act 2000 (Qld). It could only have transferred those licences to a purchaser of the land or to the CEWH. EAA could not trade this type of licence on the open market. Further, the transfer must have been approved by the Queensland government under the Water Act 2000 (Qld).

Water ‘buy backs’ (Commonwealth)

To protect the environmental, social, cultural, and economic values of the Murray Darling Basin, the Water Act 2007 (Cth) provides for implementation of the Murray Darling Basin Plan (‘Basin Plan‘). In turn, the national Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (‘SRWUIP’) gives effect to the Basin Plan. The Basin Plan, a legislated instrument, includes provision for a water resource plan for the Condamine Balonne region in Queensland, and for Commonwealth-led infrastructure projects, supply measures, and ‘water’ purchase.

The Water Act 2007 (Cth) establishes the CEWH which has the power to manage Commonwealth water holdings and administer the fund. In doing so, it can exercise Commonwealth power to purchase water rights (s105).

The Commonwealth carries out water purchases under its Water Recovery Strategy. The goal of the strategy is to divert Basin water to environmental ends, in a sustainable way.

To implement the required level of diversions and extractions without risks to property rights, the Australian Government has committed to ‘bridge the gap’ by securing water entitlements for environmental use. (Water Recovery Strategy, p5)

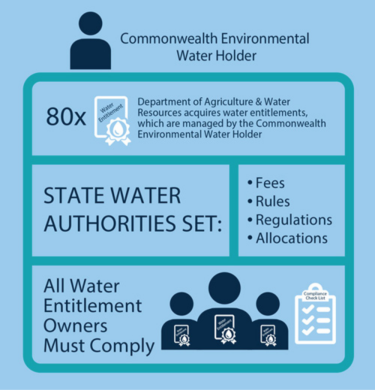

Somewhat confusingly, the Water Recovery Strategy is administered by the Department of Energy and Environment, but the SRWUIP is administered by the Department of Agriculture and Water. Under the SRWUIP, the Department purchases the water, which is then administered by the CEWH (see the diagram above). It is because the Department purchases the water that Barnaby Joyce, the then Water Minister, would have approved the EAA deal. I have not so far been able to find a legislative instrument that formally delegates purchasing authority to the Department of Agriculture and Water. (I’m not suggesting subterfuge, but point out that this is a very complex set of inter-related powers and policies.)

According to the legislative and policy framework, the purpose of government purchase of water licences is to achieve environmental goals in the Basin. The government has not simply banned licence holders from using their allocations, or cancelled licences to save water. Instead the government itself can purchase allocations for environmental purposes. When it does so, it must have regard to sustaining the other uses of water within the catchment.

Under s109 of the Water Act 2007 (Cth), the Minister may make rules regarding the purchase, disposal, or dealing with water access rights, as well as entry into contracts. There is a water trading framework in place. The trade provisions represent one of the features of the water management scheme, namely a market mechanism to allocate water to its ‘highest and best use’.

I am unsure whether the purchase of an overland flow licence is ‘trade’ as contemplated within this framework, or within Chapter 12 of the Water Act 2007 (Cth). Because the landholder and the CEWH are the only entities entitled to hold an overland flow licence, it may not be considered a tradeable entitlement. If this is the case, the overland flow scenario may technically sit outside this overarching mechanism (though I stand to be corrected).

Apart from the trade framework, generally government acquisitions must adhere to the Government Procurement Policy. Of note, the Policy excludes purchases for investment (s2.9) – and there may be an argument that the purchase of water allocation is an investment. In support of this contention, the Commonwealth Water Office has an investment framework governing its acquisition of water resources, obviously counting CEWH holdings as an investment. Further, the Water Act 2007 (Cth) and the Basin Plan both provide for the involvement of CEWH within a wider framework of trade in water entitlements. Such processes do not align with the concept of procurement per se.

The Department of Agriculture and Water website makes mention of the application of Procurement Policy reporting thresholds, together with mention of publication of contracts in AusTender. This seems to indicate that the Department acknowledges the application of the Procurement Policy, but it could also simply be an adaptation of the principles in the interests of transparency and accountability. Further, the website indicates that the government may:

consider proposals to sell water directly to the government in limited circumstances.

In short, it’s not clear to me whether the Department must comply with mandated procurement processes. It will, however, be required to comply with the Public Governance, Performance, and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth).

Observations

Not a buy back

Technically, this is not a buy back because the Commonwealth did not originally have any entitlement to the water. The Commonwealth does not have power to simply cancel the licences as they are issued under the authority of the State government. Nor can the Commonwealth command that the licences be given to it, because if it seeks to appropriate property, it must do so only on ‘just terms’. This is why the process involves purchasing the water licences for value.

Not water but rights

The Commonwealth is not acquiring water per se. It is purchasing water licences. Those licences give the licence-holder the right to use or store a particular type of water (overland flows), up to a particular volume, at a particular place. In the case of the EAA licences, it can only interfere with or collect water on those landholdings.

If the CEWH chooses not to interfere with or collect that water, it will run naturally and inevitably flow off that parcel of land and thus enlarge the total volume of available water in the system overall.

Meeting ‘environmental purposes’

The Commonwealth is authorised under the Basin Plan to acquire water licences for environmental purposes. If it had acquired irrigation licences, then the environmental purpose would presumably be to retain water in the river rather than have it irrigate crops. Presumably, acquiring overland flow permits might constitute an environmental purpose either by permitting flows to the river system that were previously blocked, or through not storing those flows and permitting them to return to the basin through various other natural means.

The Australia Institute Report says that

the Commonwealth does not retain legal ownership or any recognition of that water if it were to flow outside the farms where it was purchased. (p15)

I am not sure what ‘any recognition that water’ means. However, no one ‘owns’ an identifiable volume of physical water. Although other types of water rights may be applied to water flowing anywhere in a river system, those rights are not ‘legal ownership’ of particular water either. I am unclear as to how the acquisition of the overland flow licence is necessarily not an environmental purpose. I think it is feasible that it does serve an environmental purpose. The Department certainly asserts that it is. It is a technical question of fact whether the legislative purpose is achieved.

The Australia Institute Report also points out that uncontained overland flows may return to the river and end up in an irrigation system. They argue that if this is the case, and if the CEWH has counted the overland flows as meeting environmental targets, then this is effectively cheating: the overland flows are not going to the environment at all.

I am not sure that this assertion is necessarily correct. This is because in letting an overland flow run free, instead of containing it, there is a greater volume of water available in the system to meet committed needs (under remaining allocations).

If irrigation licences have a maximum rate of taking, then whether they use the EAA overland flow or some other source to meet that maximum, there is no change to the overall maximum take. What might be the issue here, however, is that (say, due to drought) there is simply not enough water for other irrigators to reach their maximum. In this case, the EAA overland flow might be considered to serve irrigation and not environmental purposes.

Of note, however, the purpose of the Basin Plan is to balance competing water uses within the Basin in the interests of sustaining diverse interests. There may still be an argument that enhancing the overall availability of water within the Basin supports the aims of the program.

As the argument stands, more (technical) information may be needed to confirm whether the purchased licences would assist environmental purposes. But this is not to say that the acquisition has failed to support those purposes.

Process of acquisition

If the Commonwealth Procurement Policy applies, there is a question about why there was no tender process. The Department, however, maintains that it adhered to relevant processes. Despite these assurances, there is room for clarity about what processes were required of the Department in particular, whether it was required to go to tender.

Price of acquisition

The Australia Institute outlines the negotiation process that appears to indicate that the Department paid above value. The original purchase price seems to have included infrastructure, but the ultimate contract terms do not include infrastructure and there was no adjustment to the original contract price.

On this basis, there does seem room for interrogation of the justification for the price paid.

I am less certain of some of the arguments put by the Australia Institute Report about the price based on there being no market for overland flow entitlements. They claim that the price should have been less because the Commonwealth cannot sell this entitlement to anyone but the landowner.

While I cannot comment on how valuers determine the value of such rights, it is not true to say that no market means no (or less) value. A good example of this is the recent native title compensation claim at Timber Creek. The High Court confirmed that even though native title is not a right that can be sold on the market, it was appropriate to value the right with reference to freehold land values.

The reality is that an overland flow water entitlement does have a value – even though it cannot be sold. That value is the value of the water yielded. Such a value would likely be determined with reference to the cost of gaining that water elsewhere but, as the Australia Institute Report points out, at a value lower than more reliable water entitlements. Government will no doubt have a valuation related to its environmental impact – itself not a marketable commodity.

What the ‘true’ value is, I do not know. I simply observe that this water entitlement does have value despite its non-tradeable status. The fact that the licence is not tradeable does not negate that it holds value to the Australian government.

Where the money ended up (Cayman Islands)

The question of the off-shore registration of the water licence vendor (EAA) is neither here nor there in terms of the probity of the deal. It is true that many see this as a travesty. The reality is, however, that where water rights are commoditised, they will be traded for capital gain. Capital knows no borders, and flows freely around the globe.

I cannot see that it is within the remit of the Department or Minister to inquire as to the jurisdiction of the vendor. This alone does not impugn the transaction. It speaks, rather, to a political question about the operation of the Murray Darling Basin water trading system and highlights, perhaps, to the public interest in reigning in those who may benefit from the trade.

Mr Taylor’s involvement

It is unlikely also to be within the remit of the Department or Minister to inquire into the antecedents of the company’s directorship – as a feature of decision-making under the Act. It would, rather, be a question for Mr Taylor to declare any interests he had in the company. By all accounts, he has done this.

Again, politically, there is the whiff of scandal: an ostensible connection between a minister and a profit, with added political donations thrown into the mix. But within all that has been uncovered, the sequence of events appears to stack up against the existing rules. On this basis, objections relate to the systems in place for government payment for water licences, but not to this deal in particular.

Conclusion

Unless there is evidence of ongoing undeclared benefit by Mr Taylor through the company, or of collusion of some kind between the Minister and Mr Taylor, it is difficult to suggest that the decision is somehow suspect – although there is a case for a more complete justification for the lack of tender and the price paid relative to the assets purchased. This is a question of ministerial responsibility in the interests of transparency and accountability.

The real and longer-term issue at the heart of this is whether we as a society believe that the market (in water entitlements) can genuinely save the environment. Recent devastating fish kills suggest not. A recent consultation carried out by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office reveals that stakeholders are keen to see enduring environmental outcomes from water management and this is reflected in the public outcry at the water imbroglio.

In terms of our polity, the water imbroglio raises further questions about networks of privilege between those in power and global capital – and how these networks can operate within our systems to the benefit of the already-privileged. We need to think more creatively about how to enhance institutional processes to give voice to truly democratic principles, including where the environment is a key stakeholder.